The more distant our histories, the more they are made up of tales about kings and emperors, slaughters and famines, and the less they actually capture ordinary life. So we are left with fables and epics, and propaganda repurposed as factual reference – until, that is, somebody actually excavates the slums, as explored in this story from The Guardian, UK:

“This is our archaeological handbook,” says Chris Wild, brandishing The Condition of the Working-Class in England in 1844, a muddy, thumbed paperback. “Engels.”

We take our narratives wherever we find our primary sources, and the closer they are to actual grit, the better.

This, though, is far from being the only contemporary account of late 19th-century living conditions in this part of inner-city Manchester. In 1870, the Manchester Guardian – as this paper was then known – published a series of articles on the city’s slums, opening with a scene of 18 adults and several babies squeezed round a single fireplace.

A find from the archaeological dig of the area that housed Manchester’s poor in the 19th century. Photograph: Mike Pitts. © 2012 Guardian News and Media Limited.

Only 140 years ago, and yet we are limited to a handful of texts of unverifiable reliability.

Along with Engels’ account, the newspaper’s arhive reports proved influential in the decision to investigate this site.

Every now and then, I’ve teased about archeological digs in mundane urban sites. I’ve since changed my mind – those infill locations are the only record we are likely to find of the life ordinary people actually lived, as opposed to the prismatic records of fiction or journalism yellow or otherwise. Bryan Ward-Perkins’ The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization has a truly mind-altering appendix on Roman pots.

Everything you always wanted to deduce from pots …

In particular, Ward-Perkins uses pots’ very ubiquity – their cheapness, utility in many forms, and durability as shards – to show just how much powerful evidence can be extracted from the statistics surrounding their prevalence, distribution, and condition. Though tabulations tell tales different from masterpieces, they are no less valid for doing so.

Not one to leave an investigation unfinished, the Guardian has today returned to the same streets (Miller, Dantzic and Angel) near the city’s Victoria Station.

All that remains of those slums are street patterns, a handful of reconstructed museums, records … and whatever trash we can find in the soil below.

Soon I’m kneeling on the ground in an area where Engels described “cattle-sheds for human beings.”

That slum is long gone – today nothing remains above ground but plaques.

Archaeologists are uncovering some of the worst of these slums, the subdivided cellars where people shared beds or slept in doorways while pigs ate human waste in alleys above. A collection of rubbish – bottles, a woman’s shoe, broken crockery – lies on the dirt before me.

Aside from connecting us to their humanity, these quotidian objects can tell stories about household composition, wealth, and consumption. It’s painstaking compilation work, without which we have only anecdotes, not statistics.

Little more than a century ago, this part of Manchester, then the powerhouse of the industrial revolution, was as near to hell on earth as you are likely to get in peacetime. The poor, including thousands who fled the Irish potato famine around 1850, came here for the work. Many of them would have had jobs in a large Arkwright mill on the edge of this site.

History is selective; we know what Arkwright looked like; his workers are for the most part faceless.

We have paintings of Arkwright, but not of his workers

They suffered industrial injury, cholera, TB and typhus; consumed adulterated food and contaminated water; and lived in a maze of wet, filthy, light-deprived rooms and passages.

At the end of Dantzic street was a stone-flagged area that became a playground in the 1880s (LS Lowrypainted it as Britain at Play in 1943).

Lowry was born in 1887 and began painting seriously in 1905. We can see his pictures as depicting the panoply of the vernacular, much like Brueghel.

By combining near-contemporaneous images with carefully catalogued descriptions of the finds, we can build a picture of the unknown:

The stone flags were to stop illegal excavation and sale of the soil for fertiliser: it contained the mass graves of some 40,000 paupers.

Aside from the mute testimony of forty thousand dead, that is a mine of information. Nutrition, hygiene, disease, living conditions, affordable technology – all can be gleaned by painstaking excavation, documentation, and extrapolation.

By the 1950s the houses had gone, through a combination of slum clearance and wartime bombing. Today, it’s a car park.

Curiously, that preserves it for later investigation.

Meanwhile, in 1863 the newly founded Co-operative Society opened its offices a couple of blocks away. It stayed put, so now a collection of listed buildings, one of them as recent as 1962, fills 20 acres. It is, says the Co-op, the largest regeneration site in Manchester. In 2012 its huge new HQ will rise over the Angel Meadow car park.

When the urban tomb is opened, knowledge can be gained; and if not captured then, it will be irrecoverably. It’s worth spending a few bucks – preferably the public’s bucks, not imposing this as an unfunded mandate on the unlucky developer – to take the time and fine what can be found.

It is now August, and day three of a nine-week excavation. Even within the profession, industrial archaeology remains a controversial area; some academics, especially, perhaps, historians, still question the need for digging the remains of such recent times.

“They say we’ve got all the information,” says Wild.

Maybe we have the narrative. We lack the detail – and the detail reshapes the narrative. New technology is uncovering new insights into the Roman Empire, particularly about its economy and hence about the structure of its whole society.

“But we’re testing the texts.”

The slums of Manchester are much more relevant today than Rome is, because what they were can show us how they formalized, knowledge that is directly, immediately relevant to the challenges of formalizing slums in today’s global south.

The historic maps, for example, are proving inconsistent.

The map is not the territory. The story is not the history.

Wild hopes they will be able to show the actual house plans, and he is convinced his work will reveal details overlooked by contemporary accounts.

Details like population density. Details like frequency of indoor plumbing. Location of water sources. The vitals of a city’s functioning.

Information that could be of immense value in demonstrating to the global south that their problems are not a universe apart from those faced by the global north – and, for that matter, in reminding the north that we too had these festering dens.

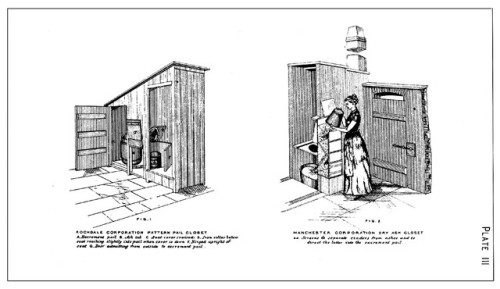

We stop at the foot of a ceramic toilet, dating from the late 19th century and cemented into a small, square floor.

Beneath, explains Wild, lies the earth of an earlier pail closet – just a bucket under a plank.

Map that against mortality rates and you can find something astonishing – like the cause of cholera – and use that for something revolutionary – like eliminating urban cholera. Or something more prosaic – like the tempo and sequence of private capital improvement – and maybe a road map to improving informal settlements in the global south.

Broken drains protrude from the side of the trench, and cellar walls made from poor-quality bricks bow under pressure. These were once homes.

From such pipes we can reconstruct the evolution of Manchester’s municipal infrastructure, and how long it took public infrastructure to catch up to catch up with private investment and exploitation. By dating the joins, we can reconstruct the sequence. We can retroactively map slum upgrading, nineteenth-century style.Properly interpreted and expressed, this could be hugely valuable information right now, for in slums are revolutions and terrorists born.

Plenty of archeological raw material is there for the learning.

Just one cubic meter of inner-city Manchester would be expected to generate more artifacts than found in a century of excavation at Stonehenge.

Think of that – think of the incredible richness of information that could be found.

“There were more people living in this part of Manchester than in the whole of Britain in the Bronze Age,” he says. “This is the archaeology of the masses.”

The ones forgotten.

The thimbles and toys, the bits of clothes and china, have a poignant association with known events, and, potentially, named individuals. With such objects Jackson anticipates links with Manchester’s People’s History Museum, due to re-open soon with a new extension – and with the Co-op’s own archive.

We are all children of slumdwellers.

“I want the younger generation to see this,” says Wild, looking across a row of Victorian lodging-house cellars. “We should help the rest of the world not to make the mistakes we made.”

Or fix them faster.